Sam Madden's world didn't end when she went totally blind 10 years ago. This award-winning equestrienne and former Ms. Country

Western Arizona is awesome. She's

OUT OF SIGHT !

Story and photography by:

REBECCA OVERTON

Reprinted here with permission of Paint Horse Journal

It is 6 a.m. as sunlight drifts past the horse show ribbons that hang on the window of Sam Madden's bedroom. Inside the tidy, two-story condominium in Phoenix,

Arizona, Sam is tackling one of the first chores of her day.

Thirty times she treks up and down the 13 stairs that connect the first floor of the condo to her bedroom and office. Her gray, longhaired cat, Muffin, bounces along with her as she exercises. Down-stairs, Sam's 4-year-old yellow Labrador retriever, Amber, waits patiently for breakfast.

After the early-morning tasks are completed, Sam goes to work in her office, where she spends the day transcribing tapes for her medical transcription business. At 4 p.m. she stops, changes her clothes and waits for her trainer, Heidi Glander, to pick her up on Heidi's way home from her job downtown.

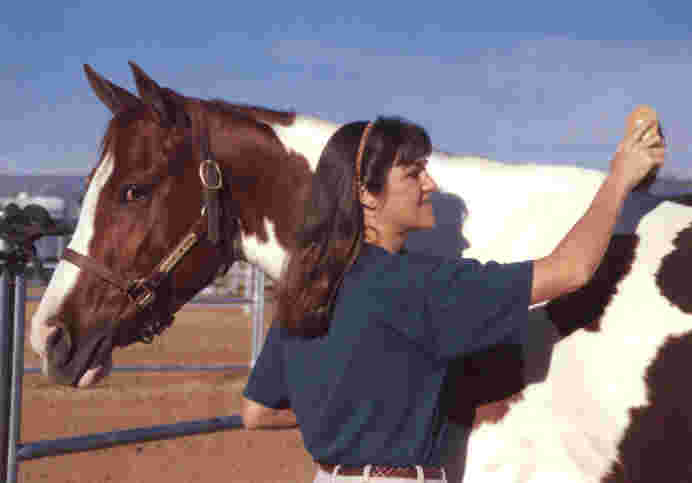

Sam plans to show the mare, whose barn name is "ZOE," on the paint circut next year.

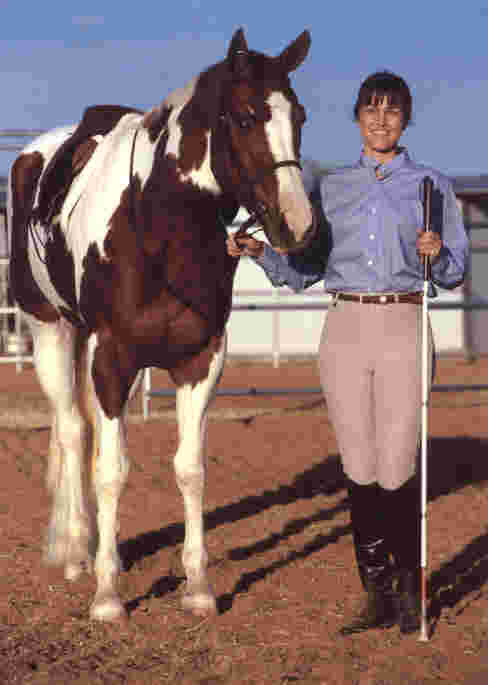

when they arrive at T&H Ranch, which Heidi owns with her husband, Terry, who is also a trainer, Sam leads her Paint Horse mare, Sugarpluum Vision, out of a stall and grooms and tacks her up. After exercising the mare, Sam takes a riding lesson, returns the Paint to her stall, and jokes with Heidi and Terry as she waits for her boyfriend, Ralph Carr, to take her home.

Despite its air of normalcy, this typical day for Sam would be atypical for most horse owners. If it all sounds pretty routine, try doing it with your eyes closed.

You see, Sam is totally blind after losing her sight to diabetes 10 years ago. But while the disease robbed her of her vision and her kidneys, the 39-year-old does what many people thought would be impossible for a blind woman-she has become a nationally recognized equestrienne who rides, jumps and, yes, even competes.

The unthinkable happens

Sam's life reads like a movie script-with one important difference. None of the events were plucked from a writer's imagination, then embellished. This is not fiction. This is fact

Sam, whose given name is Susan, was diagnosed with diabetes when she was a 17-year-old living in Cheshire, Connecticut. Although her doctor ticked off the list of possible complications-blindness, kidney failure and amputations-that might result from the disease, Sam, like most horse-crazy teenagers, felt indestructible.

"I thought it couldn't happen to me," she said.

But 12 years later, when she was 29 years old, it did.

"Within a year, I was totally blind," she recalled. "I had six major surgeries, but nothing seemed to work.

"I kept hemorrhaging, my retinas detached, then I got glaucoma in one eye and had to have an implant to drain it. After that, I developed cataracts and had to have the lens removed in the other eye.

Sam was living in Los Angeles at the time, working as an administrative assistant in the entertainment industry. Like many young women, she had dreamed of living in California, so she moved there after attending Virginia Intermont College for two years..

"I would get a regular job, then quit to do something with horses," she explained.

"For a while I exercised horses at a Thoroughbred training center in Northern California. But when my money ran out, I moved back to Southern California and worked at a 9-to-5 job to support myself."

Four months after Sam was declared legally blind, she attended the Braille Institute in Los Angeles.

"It's funny how you have to go to school to learn how to be blind," she said with a laugh.

"I learned a lot of coping skills, like cooking, and was introduced to the tools blind people can use to test their blood and give themselves injections.

"Many blind people have diabetes. Just socializing with them was a big part of adjusting.

"Eventually, I read Christopher Reeve's book, Still Me, and felt the same way about my blindness as he does about his paralysis. Even though I'm blind, I'm still the same person I always was. I'm still me."

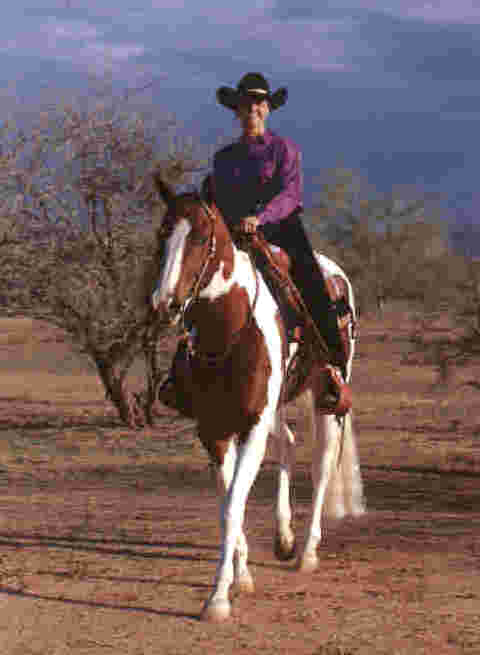

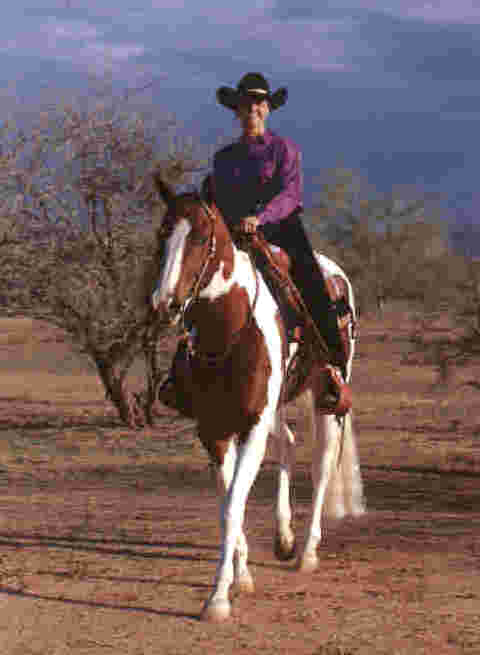

Sam and Zoe are a familiar sight at her trainers' ranch in Phoenix, Arizona. But after being placed on disability and a fixed income, Sam decided to move to Phoenix with a boyfriend.

"I just couldn't afford to live in Los Angeles anymore," she explained.

"There was too much traffic and crime, plus a lot of people where I lived didn't speak English. I remember when I first tried to get to a bus stop by myself, I wandered around my neighborhood for almost two hours trying to find it. No one I asked for help spoke English.

"That was kind of frightening."

After moving to Phoenix in 1993, Sam enrolled in Phoenix College, where she earned a degree in medical transcription and graduated with a 3.9 average. She and her business partner, Sonny Gilbert, who picks up the tapes from a group of six doctors, set up an office in Sam's home.

But Sam's kidneys were failing as a result of the diabetes, so she started visiting a hospital regularly for dialysis. With everything else going on in her life, she hadn't ridden a horse for several years.

"I didn't have the strength to do anything, let alone with horses," she noted.

But in August of 1994, she received the kidney transplant for which she had been waiting. A few months later, she began taking riding lessons at Camelot Therapeutic Horsemanship in Scottsdale, Arizona.

There she had an experience that changed her life-again.

Not a princess

When the staff at Camelot saw Sam's abilities as an equestrienne, they assigned her to a Quarter Horse thoroughbred cross named Acapulco Alibi. Sam's riding potential became even more apparent when she mastered such difficult maneuvers as flying lead changes and flying dismounts.

But one skill made Sam realize she could do even more than she had imagined.

"I remember the day I jumped Acapulco absolutely changed my life," she said. "I had no idea I was capable of such things.

"I remember coming home from the stable that day thinking of all the things I could do now that I had jumped this horse.

"It opened up a whole new world to me."

Sam's world expanded even further when she was named Ms. Country Western Arizona in 1997, a contest in which winners were chosen for their poise, beauty and ability to personify the Country Western lifestyle.

Each contestant was judged on an interview and a one-minute speech explaining why she was qualified to win.

"Because I'm blind, it's easy to ignore my competition and focus on my own performance," Sam noted.

"I could also boost my confidence by imagining the other contestants in the pageant as clad in overalls and missing their front teeth!"

Using her celebrity status, Sam campaigned tirelessly for a galaxy of charities, including the American Diabetes Association, Phoenix Children's Hospital and Special Olympics.

She hobnobbed with a variety of entertainment stars, including Randy Travis, Billy Dean, Glen Campbell, Mark Chestnut and Deana Carter. An accomplished speaker, she was a well-known face on the Donor Network of Arizona speaker's bureau, where she encouraged people to help others through organ donations.

Today, Sam is waiting for a pancreas transplant, which would eliminate the four insulin injections she must give herself daily.

"I'm a walking billboard for so many causes, such as organ donations, blindness and diabetes," she noted.

Through her words and example she also sought to inspire the handicapped to focus on their abilities. A published writer, she has written both articles and short stories, including some for children.

The Ms. Country Western title spurred Sam to find a horse she could ride in public appearances. When the directors of the pageant told her she could ride in a convertible in parades, she declined.

"That was before they knew I'm not just some pampered princess," she said. "I planned on riding a horse like everybody else!"

Six months into her reign, after placing an ad for a horse, Sam found Kenos Tomy Tutone, a 1987 buckskin tobiano gelding.

"Tommy," who was sired by Kenos Blackjack and is out of Q Ton Pep R Mint, is owned by Darelyn Nordin of Romoland, California.

"He has a wonderful personality and loves to play," Sam said, "so I decided to lease him.

"He was the love of my life for two years."

For the first six months, Sam rode Tommy in a round pen so she could learn how the gelding thought and responded in a controlled environment. The pen also provided security for Sam in case she fell off.

"I knew all I'd have to do was walk until I bumped into the rail and follow it to the gate, where Tommy would be standing," she explained.

"I could get to know his responses and work on his transitions and cadence without having to worry about steering, other than to keep him on the rail.

"I used a dressage whip in my outside hand to feel the fence, and my inside leg and weight on my outside hip to keep him over."

Soon, their skill in working together was put to the test at parades and rodeos.

"I knew if a four-ton street sweeper or the chaos of 50 people and horses doing a serpentine at a lope in a grand entry didn't bother him, he'd probably be fine under any circumstances," Sam said.

And he was.

But the team wasn't foolhardy. In parades, someone always walked next to Sam in the event of an emergency. In grand entries, she followed the voice of the rider preceding her or had Tommy ponied by another horse.

Sam performed hot laps, loping around an arena, sometimes carrying a flag, by using a small earpiece through which her coach directed her via a radio transmitter. Little did Sam know then that she would use the transmitter to take her to the next level of horsemanship to show.

Sam works out of her home, transcribing tapes in her medical transcription business. She earned her degree at Phoenix College, where she graduated with a 3.9 average.

No way!

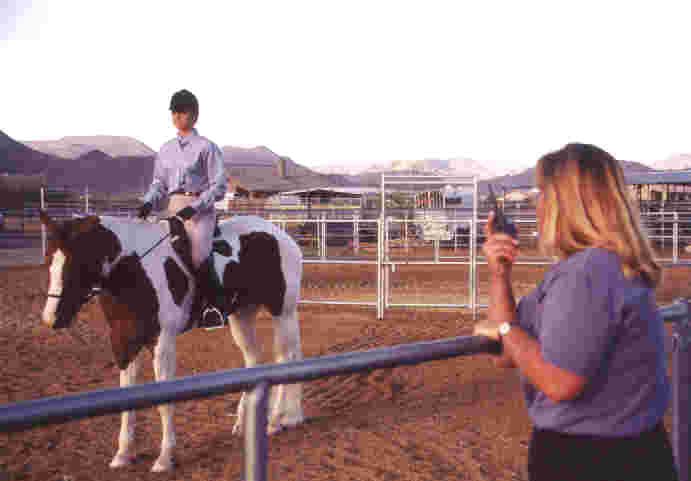

One of the prizes Sam was awarded as Ms. Country Western Arizona was a riding scholarship with horse show judge and trainer Mark Sheridan. Ater Mark saw Sam ride, he asked her if she had ever considered competition.

"Not in a million years," she replied.

Mark put her in touch with Fred Johnson, a blind equestrian in California who shows Quarter Horses in Western pleasure. With Fred's encouragement, Sam decided to take a shot at showing. Using the radio transmitter, Sam began honing her show skills with a trainer. She won her first event, a Western pleasure walk-trot class, in December of 1998.

But she didn't win the way she hoped she might her first time out as a blind exhibitor.

"It was a huge arena, and there were only three exhibitors in the class," Sam recalled. "The other two riders, both of whom were sighted, ran into each other and I won by default!"

Sam wanted to show Tommy on the Paint Horse circuit, but she didn't think he would be competitive. Still, she was convinced she and the gelding could show again.

So in April of 1999, Sam decided to take Tommy to the 1999 Pinto National Championships in Tulsa, Oklahoma. But there was one little hitch-they had barely a month to prepare.

How she did it

With the June deadline before them, Sam and Tommy revved up their schooling schedule. Trainer John Campbell worked with Tommy five mornings a week and gave Sam lessons twice weekly.

Sam's boyfriend, Ralph, stepped in as her coach. A former commercial photographer in Los Angeles, Ralph had trained horses for movies that included Rustler's Rhapsody and Ladyhawke.

Preparing for the Nationals was a challenge. In order for Ralph to give Sam directions in the show ring, they had to create a vocabulary in which each word meant something very specific.

"For example, 'left' means nothing to me," Sam explained.

"Do I bump left, turn left, cut left, yield left, pivot left, side-pass left, or pass another horse to the

left? I need to know how far left and at what angle."

Compounding the dilemma was the fact that Sam can't tell whether a horse is moving forward or backward when she is riding. This could particularly create a problem when horses are required to line up at a show.

If Tommy started to back up, Sam might think he was moving forward so she would pull on the reins, which would signal him to back up even farther.

Finally, Sam discovered she could tell Tommy was backing up because she could hear the distinctive way he dragged his toes.

Sam can tell whether she's on the correct diagonal, but she uses a different method than the one used by riders who try to do it by sight. Instead of watching a horse's shoulders, she feels the diagonal by concentrating on her own legs.

"I figured out that when my outside leg is going down, the horse's outside foreleg is coming back because he is dropping his shoulder," she explained.

"So at that point, I should be sitting."

Timing was the greatest challenge Ralph faced when he used the transmitter to give Sam directions because he had to keep ahead of the action and anticipate what her horse was going to do.

"Imagine blindfolding your best friend," Sam explained, "and directing him to drive a car. Now imagine that the car is on ice and has a mind of its own. It can move forward and backward and sideways at any angle. It can also spin around or not respond."

Anticipating what a horse will do, then reacting in time to tell Sam so she can respond, requires extreme concentration.

"You can't take your eyes off her for a second," Ralph said.

"You also have to watch 20 feet in front of her and 20 feet behind her. If she starts to wander off two steps, by the time you see it and direct her back, she can be in the middle of the arena. You have to get her back at a pleasing angle."

Sam and Ralph also taught Tommy how to jump by using a motion sensor at the base of the obstacle. when the sensor chimes, Sam knows she is 30 feet in front of the jump.

The chime helps her determine the center of the jump and her distance from it so she is ready when Tommy takes off.

Stop the show!

Their teamwork was evident at the Pinto Nationals, where Sam and Tommy entered several classes. They placed in two under individual judges, who rated them sixth in Novice Amateur Stock Seat Equitation and seventh in Senior Amateur Ideal Pinto Stock Seat, All Types.

Sam was awarded the sportsmanship award as well as an inspiration award, the first one given at the Nationals. She and Tommy became instant celebrities when they were the subject of a story on the local television news.

Sam's never-give-up attitude was an inspiration to other competitors. One told her he had had such a bad day with his horses that he pulled them from the rest of their classes.

"But after seeing Sam ride," Ralph recalled, "he said, 'I could have kicked myself I'm going back in.'"

Sam and Tommy's final event-Ideal Pinto Stock Seat-was a real show-stopper. In the middle of the class, the wire connecting Sam's earpiece to the small transmitter she wears under her jacket broke.

"I couldn't hear a thing," Sam explained. "Rather than panic and just stop, which would have been dangerous, I relied on the announced gait changes to do what I needed. I knew Tommy didn't want to rear-end another horse as much as I didn't. Left on his own, I knew he would keep me safe.

"When I pointed to my ear, Ralph knew immediately what had happened. ater asking the ring steward to stop the class, Ralph ran into the arena. He stuck his hand up my shirt and fixed the radio. What a finale!

"We even got seventh out of 17 in the class. What more ideal horse

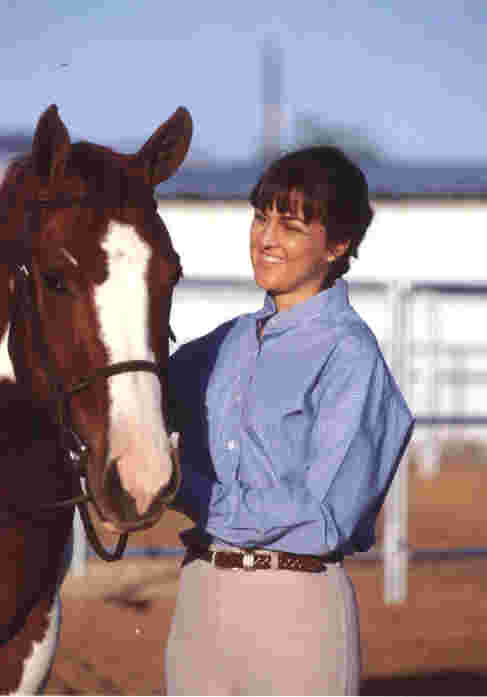

One of the reasons Sam appreciates Zoe is because the mare affirms Sam's

self -reliance "I'm a survivor, " Sam says.

could there be than one who kept his cool in that situation with his blind rider?"

Sam and Tommy ended the 1999 show season with several high-point Open honors. Sam was the East Valley Arabian Horse Association's High-Point Amateur in hunt seat pleasure as well as Western pleasure. She also was High-Point Amateur English and Western on the Arizona Pinto Horse Club's Open circuit.

In addition, she was third overall High-Point Western Novice Amateur on the Blue Ribbon circuit.

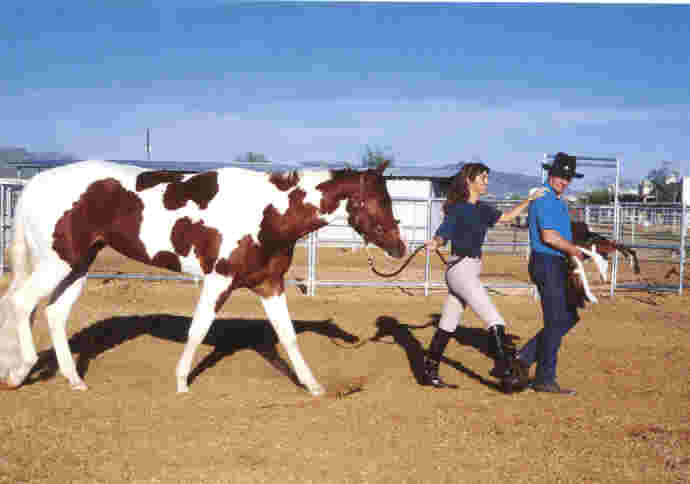

Nevertheless, Sam, who was a member of the Arizona Paint Horse Club, longed to be competitive on the Paint circuit. The time had come for her to tackle a new challenge.

It was time for Sam to buy her own Paint.

Lasso the Moon

That was easier said than done. Everyone seemed to have an opinion on what type of horse Sam should purchase. But they all agreed it should have two characteristics: It should be quiet and safe.

However, Sam didn't want a horse that all she had to do was sit on and win.

"I wanted a horse that would challenge me," she said.

It took her almost a year to find Sugarplum Vision, but the wait was well worth it. The 1996 chestnut tovero mare, whose barn name is "Zoe," was sired by Johns Ringo and is out of Auburn Indio.

With Terry and Heidi's help, Zoe is learning her way around the show ring. Heidi has already shown her at some APHA shows. She and Sam plan to take Zoe to the Pinto World Championship Horse Show this summer. Next year Sam plans to compete with her on the Paint circuit.

Meanwhile, Sam has written a story about her life, which she is hoping will be made into a movie. She wants to do all the riding in it with Zoe to show what a blind woman can do.

"I hope to interest Christopher Reeve in playing the part of my riding instructor," she said.

Sam credits her parents, Joseph and the late Ann Madden, with her ability to overcome life's obstacles. Her mother died in March of

1999.

"When I was a kid, I was kind of miffed that Mom and Dad would spend $1,000 on braces for my

teeth, but they wouldn't buy me a horse," said Sam.

"So when I was 13 years old, I bought a horse with my own money, and supported her by cleaning houses, delivering newspapers and babysitting. As the old proverb goes, my parents didn't give me a fish-they taught me how to fish.

"If they had handed me a horse, I probably wouldn't have appreciated it the way I do now. But today I not only have straight teeth, I have a beautiful horse."

Sam's motto, "Lasso the Moon," can be found at the top of her web site at http ://wildfilly.tvheaven. com. The saying was inspired by a little rubber stamp of a cowboy roping the moon that she bought in a novelty shop years ago.

"I think you can do anything you set your mind to," she said.

"I'm a survivor. If somebody tells me I can't do something, that's like waving a red flag in front of me. It only makes me try harder."

Sam is a living example of that philosophy, and of another popular quotation about something that many people find elusive:

"Most people are about as happy as they make up their minds to be."

PAINT HORSE JOURNAL. JUNE 2000